Slide Lecture of Agatha Christie’s Estate

at Greenway with Whodunit Crime Scenes

Lecture 1

Greenway, a beautiful Georgian mansion set amid 32 acres of gardens a mile above Dartmouth on the Dart River in Devon, was Agatha Christie’s holiday home. For 400 years this picturesque spot has attracted owners who cultivated its gardens, which contain over 2700 rare specimen plants. A Tudor dwelling was built in 1535 and was replaced with the current Georgian residence in 1791. Dame Agatha purchased the house in 1938 and in 1959 transferred the estate to her daughter Rosalind Hicks, who owned it jointly with her second husband Anthony Hicks and her son Mathew Prichard. In 2000 the Hicks family gave the house and grounds to the National Trust. The gardens were opened to the public in 2002 and the house will open in 2009. Our virtual tour will include pictures of the interior of the mansion with Christie’s furnishings as well as the gardens.

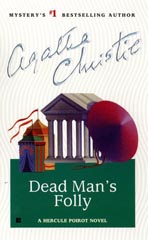

Apart from Greenway’s historical, architectural, and horticultural importance, Christie set two novels and at least one short story at Greenway: Dead Man’s Folly, Murder in Retrospect (aka Five Little Pigs) and “The Shadow on the Glass.” It is possible to trace the action of her plots on site because Christie adhered closely to the actual physical setting. As this slide tour of Greenway progresses through the house and grounds, crime scenes from all three stories will be visited.

Lecture 2

The whodunit whose action can be most closely traced at Greenway is Dead Man's Folly, in which murdertakes place during a garden fetê while a treasure hunt devised by the detective novelist Ariadne Oliver is in progress. When she suspects foul, she summons Hercule Poirot to prevent disaster. Join Poirot as he strolls about the garden looking for clues and chatting with pottential villains.

Lecture 3

The Privy Garden at Greenway, a small formal garden enclosed by high holly hedges with only one enterence, is the scene of a double slaying in this vintage country house murder mystery. Action occurs both inside the house and in the grounds. The enigmatic Mr. Harley Quin assists Mr. Satterthwaite to overcome the superstitious spell cast by a resident ghost and preceive the prractical solution to the crime.